- Home

- Ron Fournier

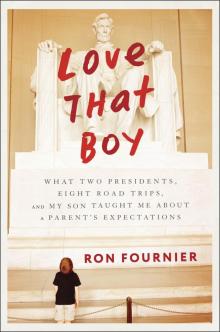

Love That Boy Page 5

Love That Boy Read online

Page 5

—

Ever hear the metaphor of a boiling frog? If a frog is placed in boiling water, it will jump out and escape, but if it is placed in cold water that slowly is heated, it won’t notice the danger and will be cooked to death. The anecdote is used to describe the inability or unwillingness of people to react to drastic changes that occur gradually. Holly was a boiling frog.

When she started middle school, our eldest daughter suffered nervous episodes over her grades and homework, sometimes to the point of vomiting. We chalked that up to teenage angst. Lori thought Holly would learn to manage her nerves; I thought she would toughen up. Lori did what she could for Holly; I did what I could from the campaign trail, where I spent large chunks of Holly’s middle school years. We had no doubt things would work out. After all, Holly was a great kid.

At Yorktown High, a public school located in the affluent suburbs just outside Washington, our oldest daughter drifted away from elementary school friends and began spending most of her time with a new friend, a girl from a single-parent home who struggled, like Holly, with expectations at home and at school.

Holly was driven to excel. Lori tells a funny story about the day Holly brought home a pile of vole bones encased in owl vomit, with instructions from her science teacher to assemble the rodent remains into a standing skeleton. Lori and Holly quickly assembled the bones—foot to ankle to thigh to hip to chest to skull. Try as they might, though, mother and daughter couldn’t get the skeleton to stand.

After several hours, Lori sighed, “We did the best we could. Your teacher will just have to accept it lying down.”

Holly said, “No. She said she’ll mark us down a full grade if it doesn’t stand up. I don’t want a B.”

“Nothing wrong with a B,” Lori chuckled. “Your dad got plenty of them, and he did all right.”

Holly sobbed, “I can’t get a B.” She was inconsolable, but the vole and Lori were just as stubborn. Holly got a B.

While Holly was obsessed with getting great grades and being admitted to a top college, Lori and I didn’t care much about where she went to school. We did fine with our commuter-college degrees. So if not us, what drove Holly?

I suspect part of the problem was her genes. Her father is insanely competitive and comes from a family of win-at-all-cost warriors. Holly could have benefited from more of her mother’s genetic influence. Another culprit was the culture of the Arlington County School District, an affluent and nationally recognized public school system, where parents, teachers, and peers demanded excellence.

Years later, Holly said, “It wasn’t so much what my teachers wanted from me, because what they wanted was high test scores and good grades, and I got those anyway. It was what they weren’t giving me: any sort of warmth or any sort of caring about me as a person.” Holly had missed a lot of high school because of her nerves, and her nerves were on edge because of problems at home. Holly was fighting with Gabrielle, with whom she shared a room, and we responded to the fights by yelling at both girls. Gabrielle shrugged off conflict. Holly internalized it, and slowly convinced herself that she wasn’t loved or liked.

I should have seen this coming. A friend of mine, Scott Gilbride, had a daughter who was drowning in her own expectations. Mary Lacey Gilbride was a star athlete and straight-A student who played pickup basketball on Monday nights with several men, including me and her father. One night, while we watched Mary Lacey warm up with a blizzard of three-point shots, Scott asked about Holly. Our girls were about the same age, and we liked to compare notes. “She’s fine,” I said. “But, boy, she’s getting moody. She’s fighting with her sister and mom all the time.”

“Daughters are glorious,” said Scott, the father of three girls, “but they’re never easy.” A few weeks later, after three long and sloppy pickup games, Scott confided in me, “Mary Lacey has talked about killing herself. We don’t know what to do.” He fretted about the drugs prescribed to her—none of them had worked for long. He complained that mental health research was underappreciated and underfunded. “We need more research into mental illness,” Scott said, “and parents need to be taught how not to miss the signs of severe depression.”

I had missed them. Lori and I thought we just had a snotty teenager on our hands. We didn’t know Holly was depressed. Neither did school officials. “None of those teachers asked me if I was okay when I missed all that school,” Holly said of her middle school issues. In high school, “teachers spent their time helping the struggling kids or the bad kids. Meanwhile, I’m getting good grades and being quiet and nobody paid attention to me until…” Holly paused. “It was almost too late.”

It was almost too late. Just writing that sentence gives me a chill. In mid-January of Holly’s senior year, I was working out of the house on a school day when the phone rang. I answered it. “Mr. Fournier?” It was Holly’s counselor. “Your daughter’s in my office, sir. She’s been talking about hurting herself.”

“What do you mean, hurting herself?” I had no clue.

“She’s told a teacher and a friend that she’s thinking of killing herself.”

Urgently, we got Holly help. Her mental health stabilized enough that, just seven months after her breakdown, we drove two hours from our home and dropped her off at James Madison University. And prayed.

—

In elementary school, Tyler asked Lori what she thought of his second-grade teacher. “She is nice,” Lori replied. Tyler’s eyes, two sea-blue globes, widened in alarm. “Mom, you don’t know her!” he protested. “She has a dark side.” We laughed, which might seem odd, but we knew he was being hyperbolic. The teacher wasn’t evil; she simply was frustrated with Tyler’s academic progress, and for good reason. Despite his obvious intellectual precociousness, Tyler was sinking in school.

His IQ is higher than that of 98 percent of the population, nearly genius-level. His recall of facts is nearly perfect, especially with regard to his favorite topics. He entered elementary school with an adult-level vocabulary. All this increased our expectations for Tyler, his teachers, and ourselves. Why isn’t this little genius getting better grades?

He rarely completed assignments, and often didn’t start them. During the teacher’s lectures, Tyler stared out the window—when he wasn’t interrupting. Reading came hard to him until he discovered video game strategy guides, and for the longest time, that’s all he would read. Most alarming to Lori and me was his inability to put thoughts on paper. The kid couldn’t write. Part of the problem seemed to be fine motor skills. He simply couldn’t manage the act of holding a pencil and directing his hand to create letters, words, and sentences on paper. But even when we asked him to dictate to us, Tyler froze. He could talk in full, rich paragraphs every waking minute until we said, “Okay, it’s time for homework.”

The teacher blamed it on his attention issues and recommended to Lori that we hire a nutritionist. The nutritionist put Tyler on a diet of organic foods, none of which we could get him to eat. From the time he graduated from baby foods, Tyler’s diet had consisted of just five items: Velveeta macaroni and cheese (the kind with shell noodles—no other shape would do), hot dogs (only Oscar Mayer “classic”), fish sticks, bananas, and chocolate Pop-Tarts. That was it. Nothing we did could convince Tyler to try something new, particularly organic hot dogs and gluten-free macaroni and cheese.

His aversion to new food mystified us, but we shrugged it off. Some kids are picky eaters. He’ll grow out of it. We didn’t recognize that his sensitive palate was a red flag. Instead, we focused on a question that had long divided us: Do we put him on attention-deficit medication? Lori and I fought over this more than almost anything else in our marriage. She wanted him medicated. I didn’t.

“If he had diabetes or high blood pressure, you wouldn’t think twice about giving him drugs,” she told me. Lori was singularly equipped to understand the depths of Tyler’s problems because, with rare exceptions, she was the only parent who struggled with him over homework, met with teachers

, and took him to doctor’s appointments.

She saw Tyler as a revving engine that couldn’t slow down. Lori cried whenever she thought what life must like for Tyler amid such inner turmoil. “You have no idea what he’s going through,” Lori told me. “You have no idea how badly he needs help.”

My opposition to attention-deficit medicine was purely visceral, informed by parental hate-reads and blind machismo. I declared, “We’re not drugging my son.”

We drugged my son. He was finishing second grade when I finally conceded that Tyler couldn’t learn if he couldn’t focus, and he couldn’t focus without medication. Lori worked aggressively with the doctor, constantly tweaking medication types and levels. Too little and the medication didn’t help. Too much and the drugs made Tyler flat, like a zombie. His prescription changed every few months as his chemistry adjusted with age. Lori’s advocacy stopped Tyler’s academic slide, but he struggled in school for many more years, especially with the writing, until Dr. Quinn’s diagnosis—and our guilt trips—put him on a better path.

—

Academic expectations complicated an already challenging environment for Tyler. Parents pressured political leaders to raise test scores and college admission percentages. Politicians pressured school administrators. School administrators pressured teachers. Teachers pampered the brightest students and buoyed the failing ones, which left little bandwidth for kids like Tyler in the mushy middle. His disruptive behavior, as much a part of Tyler as his autism, didn’t win any friends in the teachers’ lounge.

Academic expectations robbed Holly of the emotional support she needed in high school. Her teachers and parents were focused on her grades, not her mental well-being. We dodged a bullet. Holly graduated from college, started a career, and got married. She now works for the Detroit News, thriving professionally and personally.

Lori and I were blessed with the means to hire tutors and therapists to fix what the schools broke or couldn’t fix. For other parents, the stakes and costs are much steeper.

In our lust for academic excellence, we forget the pride and promise of our children’s first day of school. It is not their destiny on that September day to be the smartest or most accomplished children. It is their time to learn. To learn to be their best, not their best impression of what we want them to be. The next parent who Googles “Is my 2-year-old gifted?” should get a curt response: “Your 2-year-old is a gift.”

POPULAR

“I Thought I Could Buy Them Friends”

Cove Neck, New York—This isn’t right. It is 55 degrees and sunny, a perfect late autumn morning in suburban New York, and I’m on the road with my boy. But something’s off. The electronic navigator that guided us 250 miles to the former hometown of Theodore Roosevelt is now telling us in a soothing robotic voice to stop here, in front of a 1,000-square-foot ranch house with slate-gray siding and butter-yellow shutters. “You…have…arrived.” Stationed at the edge of a burnt lawn is one of those bent-over wooden garden women. I tell Tyler, “I don’t think this is TR’s house.”

“No joke,” Tyler laughs. “I’m bored. Just kidding.” On the ride here, Tyler had complained repeatedly about being pulled away from his video games and books, until I finally told him to knock it off. Now he’s got me laughing at myself. I reprogram the navigator for 20 Sagamore Hill and we drive another 10 minutes.

Sagamore Hill National Park is 83 acres of forestland, meadows, and salt marshes overlooking Oyster Bay Harbor and Long Island Sound. In addition to nature trails, a boardwalk, an icehouse, and a pet cemetery, the property includes two homes. The grandest was completed in 1886 under Theodore Roosevelt’s direction and expanded in 1905 to add the largest of its 23 rooms, the North Room. Tyler is fascinated by the menagerie of animal detritus, including elephant tusks, a stuffed badger, and a polar bear rug, all nods to Roosevelt’s passion for hunting. Tyler observes with a laugh, “This is a zoo for the dead.”

We’re here because Roosevelt is Tyler’s favorite president, though I’m not sure why that is. On the drive, I had asked Tyler whether he identified with Roosevelt because TR was a sickly child. Tyler stared out the windshield at the approaching Manhattan skyline. “No,” he mumbled.

Well, was it because, as a boy, TR was taunted by classmates?

“No.”

Was it because both of them loved animals and science and history?

“Nope.” Tyler cut me off. “He was just cool, man. Kids don’t have to have reasons. He was just a cool dude.”

We start our tour at the smallest building, closest to the parking lot. The park’s museum is in the Orchard House, a Georgian-style mansion built in 1937–38 by Ted Roosevelt Jr. A musty smell and a well-worn gray carpet greet us at the door, yielding to high-ceilinged rooms stuffed with exhibits. Next to the first interior door is a clear plastic case, empty but for a crinkled five-dollar bill. A sign reads DONATIONS.

The first exhibit commemorates February 14, 1884, the day Roosevelt’s beloved mother, Martha Bulloch Roosevelt, and his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt, died within hours of each other. Roosevelt wrote in his diary that night, “The light has gone out in my life.” He hardly spoke of Alice again.

A knot of tourists at the exhibit share funereal whispers until startled by Tyler’s booming voice. “Talk about a hard day!” he laughs. “Two for the price of one!” This is what they call a learning moment, exactly what Lori had in mind when she conceived of the road trips. Help him read people, she said, and understand when jokes are appropriate and when they’re not. Yeah, well, that’s going to have to wait until we get back to the hotel.

I nudge him, say, “Be respectful, son,” and nod apologetically to the tourists.

We move quickly to the exhibit on Roosevelt’s childhood—his debilitating asthma, his scrawny build, and a reference to two boys who bullied him on a camping trip. I think of Tyler—his Asperger’s, his social awkwardness, and the bullying he is starting to experience. It’s not physical, at least as far as we know, but middle school is the age at which kids are most likely to be the source and subject of verbal abuse. At 13, even as an Aspie, Tyler is now self-aware enough to understand that he’s a target.

I delicately ask, “What do you think?”

He chuckles. “I think you’re trying too hard.”

We leave the childhood exhibit for one about Roosevelt’s time in the American West—buckskins, branding irons, buffalo guns, and other tokens of wide-open spaces sealed inside a glass box. There’s a box for every chapter of Roosevelt’s expansive life: fighting political patronage via the U.S. Civil Service Commission, exposing corruption as New York’s police chief, preparing the nation for war at the Navy Department, leading the Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War, and returning home a hero to defy the New York political machine and become a reformist governor. Wanting him out of Albany, GOP bosses made Roosevelt the party’s vice presidential nominee in 1900. The move backfired when an anarchist assassinated President William McKinley in September 1901, making Roosevelt the nation’s youngest-ever president at age 42.

The foreign policy exhibit, titled “Stepping onto the World Stage,” triggers a thought. Roosevelt led the United States away from its isolationist instincts and into the global community, stronger and more confident than at any previous time in its history. Tyler is just starting to learn how to emerge from his shell and embrace the broader community. I excitedly share my theory: “America had Asperger’s and TR showed the country how to cope.”

Tyler chuckles again. “Nice try.”

Desperate now, I point to a picture of an adoring crowd of thousands cheering the toothy Roosevelt. “He was sick and mostly alone as a kid but then grew up to be wildly popular. Do you want to be popular, buddy? Do you want more friends?”

“That is not why he’s my favorite president. He’s my favorite president because he kicked butt!”

“Do you want to kick butt, buddy? Roosevelt muscled up so he could fight bullies. Do you want to muscle u

p?”

“No,” he says with a shrug.

“But—”

“Dad, stop.” His tone is flat, firm. For a moment it feels like we have reversed roles and my son is now teaching me. He says, “Remember the Freaks book?” Just 10 days ago, Tyler brought home from school a memoir, Freaks, Geeks and Asperger Syndrome, and pointed to a passage. “First of all,” the 13-year-old author, Luke Jackson, wrote, “the biggest gem of advice I can give you on this subject is never force your child to socialize.” The boy author added, “Most AS and autistic people are happy just to be by themselves and do their own thing, rather than going out and meeting people and having people around for social occasions. On the contrary, this makes them nervous—at least it does me and other AS people I know.”

“Remember the book?” Tyler repeats.

I nod as I stare at the picture of Roosevelt. “I remember, buddy.”

“I’m happy by myself, Dad. You don’t have to force things so much.”

Tyler and I were park rats. Our neighborhood in northern Virginia was flush with playgrounds, and we loved to explore them after work and on my days off. Tyler had nicknames for each one: “House Park,” “Super Park,” “Yellow Park,” and so on. I would crawl with Tyler up and around the hard plastic equipment, or we would play imagination games together. But more often than not, Tyler would play without me, which is why I always brought a book. From a nearby bench, I’d read a few paragraphs and watch Tyler. Read, watch. Read, watch.

I wanted to keep him safe, of course. But I was also interested to see how Tyler interacted with other kids.

Which is why I can’t shake the memory of the day, years ago, when I took Tyler to a park near my parents’ retirement community in Florida. There was another young boy playing on a massive toy pirate ship. Tyler climbed aboard and started talking about animals. “Do you know the world’s largest rodent? How about the smallest mammal? I saw a manatee…” His rapid-fire delivery caused his words and sentences to flow together. It was a muddle of minutiae that clearly irritated the other boy, who cupped his head in his hands and shouted, “My ears hurt!” Tyler continued jabbering. He didn’t know why the boy ran away. I sure did.

Love That Boy

Love That Boy